“My hands read a Braille map hewn from bone, starting with my hollow breasts threaded with blue-vein rivers thick with ice. I count my ribs like rosary beads, muttering incantations, fingers curling under the bony cage. They can almost touch what’s hiding inside. My skin slopes down over an empty belly, then around the inside sharp curve of my hop bones, bowls carved out of stone and painted with fading pink razor scars. I twist the in the glass. My vertebrae are wet marbles piled on top of the other. My winged shoulder blades look ready to sprout the feathers.”

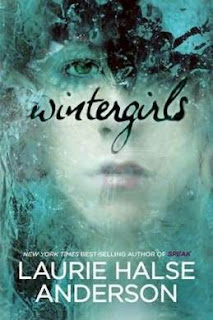

-Wintergirls

Wintergirls shows a generation of young women how our entire culture can prove toxic to girls' life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. Inevitably, Wintergirls will be referred to as "the eating disorders book" in Laurie Halse Anderson's canon, just as Speak will be distinguished as "the rape book" and Chains will be reduced to "the slavery book." This is a shame, because there is so much more to each of these novels than a simple "problem novel" label would imply. The plot, in a nutshell: in the aftermath of her best friend Cassie's death, Lia struggles with guilt over ignoring Cassie's pleas for help and with her own body as she attempts to reach the finish line of her anorexic weight loss goals, gradually realizing that "winning" means death, not survival. Yes, eating disorders and cutting play an important role in Wintergirls, but Anderson's vision is much more comprehensive.

The number of girls we are introduced to in the novel either directly or through the anorexia discussion boards that Lia frequents is legion, and while the physical acts of mutilation and starving oneself near to death are difficult enough to read, Anderson puts the reader deep inside Lia's mind to feel the painfully twisted logic that motivates her actions. Lia's conflicts with parents, stepparents, stepsiblings, friends, acquaintances and doctors create a complex web of pressures. The novel is filled with heavy duty (but never heavy-handed) allusions to fairy tales (the Sleeping Beauty, etc.) and Classical myth (Persephone), indicating that the schizoid cultural ideals of femininity (ex. take control of your destiny, yet remain passive) that straitjacket Lia aren't just late 20th/early 21st century phenomena; they lie at the very roots of our Western culture.

In the classroom, Wintergirls would prove useful both in regular classroom study but I would not recommend it for lit circles. With this novel a lot of debriefing and discussion should take place because of the events of the novel. Eating disorders and the issue of cutting is not something to take lightly, especially with a group of adolescent girls. Some kind of research project on eating disorders and/or depression would be a good parallel or follow-up with this book. There are a variety of other issues present in the novel, including mental and emotional stability, as well as relationships. Lia’s relationship with the adults in the novel, and also with Elijah are not exactly healthy, and their deterioration mirror hers physically. The relationship Lia has with Cassie is especially volatile and would also need some critical analysis. I believe that talking about these delicate and complicated issues as a class would be the best way to allow for students to voice their opinions and thoughts.

A personal reflection or journal component to the unit would also prove beneficial for the students so that way teachers could monitor students’ reactions, and address any red flags or points of concern they are noticing. I think it would be neat to examine how the boys feel about the text, and perhaps create a gender debate about the issues in the book. The male population may not be as sympathetic to Lia as the girls, or perhaps they will be more so. It would be extremely interesting to get both views. I would also want them to compose a short essay or journal response on how relationships with people can be both beneficial and harmful. In addition, I would ask them to outline two different relationships they have in their own lives, one that is beneficial and one that is harmful and how it affects them emotionally.

Laurie Halse Anderson was born on October 23, 1961 in Potsdam, a place located in northern New York State, near the Canadian border. Growing up, Laurie had always loved writing but did not consider to be more than a hobby. When Laurie began to write seriously, and for profit, she accumulated an assortment of rejection letters, most of which were severely discouraging and intimidating. She joined the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators and found a supportive critique group, which helped her to keep writing instead of giving up. Anderson actually began her career as a picture book writer, and still writes them to date.

Laurie is best known for her YA novels, specifically the award-winning Speak which was a New York Times bestseller and a National Book Award Finalist. Her most recent book, Wintergirls, also debuted on the New York Times bestseller list and received starred reviews from Publishers Weekly, School Library Journal, Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books, among others. The novel was also the focus of much media attention for its unflinching and raw perspective on eating disorders. In 2009, Laurie received the Margaret A. Edwards Award for Lifetime Achievement for her body of work for young adults. In 2008, she also received the prestigious ALAN Award, which honors those who have made outstanding contributions to the field of adolescent literature. She is also is the official spokesperson for the American Association of School Librarians' (AASL) School Library Month (SLM) 2010 celebration.

Her books appeal to students because they address issues and conflicts that adolescents are facing in their own worlds, and she does it in a way that is poignant yet serious, controversial yet gripping.

Anderson’s official website has biographical information, news, and links to R\reviews of the book, and a video of Anderson commenting on her latest novel

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS:

• Lia’s mother tells her: “Cassie had everything: a family who loved her, friends, activities. Her mother wants to know why she threw it all away.” According to Lia, asking “why” Cassie died is the wrong question. She says to ask “why not.” What do you think she means by this? Which do you think is the right question to ask? Is there an answer to either?

• How would you relate the two epitaphs in the beginning of the novel to the novel itself? How do they apply to Lia and her situation? What about the title of the novel, Wintergirls?

• Lia is extremely particular about the names she calls her family members (“Jennifer” instead of Stepmom; “Dr. Marrigan” instead of Mom; “Professor Overbrook” instead of Dad). What does this reveal about what she thinks of her family members. Do you think this is an accurate representation of how some students feel about their parents? Is it okay that she (or they) feel this way?

Thanks for the introduction to the book, "Wintergirls". The quote was captivating. I appreciate your analysis of overly catagorizing books into topics that there is a great deal missed in this simplification process. This seems similar to what happens when we do this with people as well.

ReplyDeleteNancy

I recently read this novel with mixed feelings. I would be reluctant to teach this as a class text, just because of the serious nature of the subject matter. Anorexia and bulimia are better known and better understood than when I was young; however, the pressure of the culture to be slim and the pressure some girls place upon themselves to be "prefect" leave some students ripe to fall into eating disorders. A cousin of mine was bulimic for some years and got the idea from an Ann Landers column intended to warn of the dangers of this disease! Your point about using Wintergirls in lit circles is well taken, though. I think this novel has important things to say and think about. I'm just unsure about how to use it in a school setting. I think I'm going to use this novel in my annotated bibliography, so I'll definitely be thinking about this issue some more. Thanks for a very interesting post.

ReplyDeleteThis book is definitely on my list. I wonder how it would go over in a classroom. When I was observing at Westhill last senester a students discussed her eating disorder in a college essay she wanted me to help her with and yet she felt too nervous to share this with her teacher. Therefore, I agree that if this book is used in the classroom, the teacher has a lot of work to do, unpacking this extremely delicate issue. This book might better serve as a personalized suggestion. (I could've suggested it to this student if I knew about it then). Thanks for all your helpful information!

ReplyDelete-Jilian

All of our books are so scandalous! Teen literature really brings out the Jerry Springer in us, eh? :)

ReplyDeleteI like the idea of using a journal with this book, and other books that deal with such "unhappy" materials. Class discussions worry me at times, mainly because they take a certain dynamic/relationship to feel safe enough to share/disclose (which could potentially occur when reading something that affects so many teens). With a journal, the answers are between the writer and whoever is selected as the reader, and it gives space to work out thoughts. Also, if it is a class-directed journal, the teacher could be providing information about who to turn to for help in addition to the outlet of the journal.

Very nifty, Kallie!